Posted Nov. 21, 2004

Posted Nov. 21, 2004

Updated Dec. 3 with resistance and power calculations -- oh yeah! The pull of AWD: Christini Venture Long Travel In cars, all wheel drive improves traction and stabilizes cornering. Those both seem like good attributes in a mountain bike, and Christini Technologies, Inc. is out to prove it. A few weeks ago pro gravity racer Gayle Dahlager loaned me her Venture Long Travel. I picked it up on a Friday night to ride Saturday morning. All evening I wondered what it would feel like. It just seemed so ... different. I'd heard of the bikes, but everyone I talked to said they were strange, whether or not they'd ridden one. I decided not to sweat it. I'd just hop on and wring it out like it was mine. How it works

A bar-mounted lever lets you engage and disengage the AWD system. Pulling the cable releases the clutch in the rear hub, allowing the ring gear to remain impassive while the rear wheel gets all spinny.  When you hit the little button that releases cable tension, you don't necessarily send a pulse of power to the front wheel. Because of a slight gearing differential between front and rear, the front wheel doesn't receive power on smooth, level ground. It just coasts along like normal, with a one-way clutch allowing the hub to out-spin the gears. The front wheel actively engages whenever the rear wheel speeds up (i.e. slips on a climb) or the front wheel slows down (i.e. hits an obstacle or pushes through a corner). The cornering effect, says company president Steve Christini, resembles an Audi Quattro. As an Audi lover, that makes me rub my hands together and say, "Ex-cellent!"

When you hit the little button that releases cable tension, you don't necessarily send a pulse of power to the front wheel. Because of a slight gearing differential between front and rear, the front wheel doesn't receive power on smooth, level ground. It just coasts along like normal, with a one-way clutch allowing the hub to out-spin the gears. The front wheel actively engages whenever the rear wheel speeds up (i.e. slips on a climb) or the front wheel slows down (i.e. hits an obstacle or pushes through a corner). The cornering effect, says company president Steve Christini, resembles an Audi Quattro. As an Audi lover, that makes me rub my hands together and say, "Ex-cellent!"

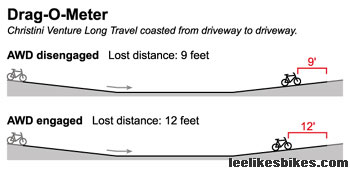

Specs of note Suspension: The Venture Long Travel gets four or six inches of rear travel. Mine was set to six of course. A single pivot lines up with the middle ring, and the stays drive a swing link, which drives the Manitou Swinger 3-way air shock. It feels like any middle-ring-height single pivot bike, which means the rear end kicks on rough single-ring climbs and jacks under braking. My refined palate found it a tad crude, but it works fine. Most riders would be stoked. Fork: The Christini comes with a proprietary White Brothers VT 1.3 fork, which accommodates the AWD system and 80-130mm of travel. This one was dialed all the way out in *extreme long travel* mode. I felt a lot of bushing play in the parking lot, but I didn't notice it on the trail. The fork is plush and smooth. I didn't give it a thought. It just worked, which is what you want. Geometry: A 69-degree head angle is steeper than I'm used to, but slack and stable enough for fun descents. The steep 72-degree seat angle perched me above the cranks and made pedaling feel good. This is a perfect spec for a bike that will earn its turns. Tires: Gayle's bike wore a tattered Maxxis Mobster Super Tacky in front and a fresh Maxxis High Roller Semislick Super Tacky in the rear. The sticky rubber made these tires feel pretty slow, but they hooked up well. The semislick rear was pretty impressive, in both AWD and RWD. It broke loose easily under braking, but once I set it on edge it hooked like a full knobby. Heft: I'd estimate the bike's weight at about 30 pounds, which is normal for a mid-travel all-mountain bike. The AWD system comprises 2.3 of those pounds. Overcoming resistance I tooled around my neighborhood with the AWD disengaged. The bike felt like any other mid-travel bike with sticky tires: decently nimble but kind of slow. When I engaged the AWD, the thing seemed to erupt in mechanical noises, and it slowed noticeably. Without a doubt, the AWD makes some racket, and it affects the bike's ability to coast. The question was, how much difference does it make? I devised a Cooter way to measure the increased rolling resistance:  I did sort of a pendulum experiment. I rolled down my driveway, across the street and up the opposite driveway. In theory, if there was no resistance at all, I'd end up with my wheel touching my neighbor's garage door. The distance I lost on each pass would give me a relative measure of my lost energy.

I did sort of a pendulum experiment. I rolled down my driveway, across the street and up the opposite driveway. In theory, if there was no resistance at all, I'd end up with my wheel touching my neighbor's garage door. The distance I lost on each pass would give me a relative measure of my lost energy.

With the AWD disengaged I lost 9 feet. With the AWD engaged I lost 12 feet. That's an increase of 33 percent, which is tremendous. That said, you're most likely to engage the AWD in deep mud/snow or on a steep climb, both situations where rolling resistance is a tiny portion of your total effort. If you're coasting on flat ground, you'll probably have the AWD turned off. On descents the extra drag definitely slows you down, like engine braking on a motorcycle, but if the AWD improves handling the drag won't be such a ... well ... drag. Added Dec. 3, 2004 Since I posted this story, I've discovered an excellent spreadsheet by John Snyder that calculates the power required to ride in various situations. These results might not be perfect, but they're as close as I can get.  Coasting resistance is a small part of the complete power equation. This chart shows the power required to ride at different speeds, inclines and acceleration rates.

Coasting resistance is a small part of the complete power equation. This chart shows the power required to ride at different speeds, inclines and acceleration rates.

Maintaining speed on flat ground doesn't require much power, so the AWD engagement has a relatively large effect. Steeper hills and harder acceleration require more power, which makes the AWD's resistance relatively smaller. Details: Here's my raw data and source info. End new section Trail testing I only got one ride on the Venture, but a loop at White Ranch in Golden, CO subjected it to a range of conditions. Climbing over round rocks: The trail begins with a zig-zag up a rocky stream bed. I usually have to work pretty hard here, going around some of the football sized rocks and lunging over the others. The rocks are spaced about a wheelbase apart, which makes the timing tricky, and it's hard not to let your front wheel deflect off the odd-angled hits. I put the Christini into the middle ring, crouched over the middle of the bike and just pedaled. The bike tracked right over the rocks, despite some feedback from the rear suspension. The coolest thing was, when the front wheel hit the rocks it didn't deflect at all; it felt like it crawled right over them. Moderate climbing on hardpack: When I spun up an easy grade the noise drove me crazy. It made the bike feel cheap, and I just knew it was robbing power. I turned the AWD off and climbed like normal. (Regarding the noise, Steve Christini says: "Sounds like the drive train on that bike needs a little different lube as you really shouldn't be able to hear the gears more than a little whiring sound. We've found that when it's cold, the aluminum gearing likes a different lube than when it's warmer.") Climbing up wooden stairs: The trail drops across a creek then climbs the opposite bank. Railroad ties step up one side of the trail, while a smooth board goes up the other side. I engaged AWD, left it in the middle ring and charged straight up the steps. To my surprise, the front wheel crawled right over them. I didn't make the entire section due to weak sauce and bad timing, but the AWD definitely made it more possible than with a normal bike. Steep climbing: The climb skirts the side of a very rocky mountain. It's steep, loose and rough. I engaged AWD in the trickiest sections and the bike just crawled right up the trail. I noticed the front wheel doing its high-powered thing. I didn't notice any noise or increased resistance. Climbing in mud and snow: Yes. The grade was moderate, but the surface was slick. The Venture just grabbed along. The front tire did catch ruts differently, like it wanted to latch onto whatever it touched and marry it, so I had to relax more than usual and let the bike go where it wanted.  Sprinting: On the way down I slung out of a few turns and got on the gas -- hard. I'm used to a certain amount of fishtailing on any bike, but that trait was absent on the Christini. I pedaled as hard as I could across coarse-sand-over-hardpack, and the bike hooked up 100 percent. Very cool. It would be interesting to test heart rate vs. speed in both AWD and RWD. Oh well, maybe next time.

Sprinting: On the way down I slung out of a few turns and got on the gas -- hard. I'm used to a certain amount of fishtailing on any bike, but that trait was absent on the Christini. I pedaled as hard as I could across coarse-sand-over-hardpack, and the bike hooked up 100 percent. Very cool. It would be interesting to test heart rate vs. speed in both AWD and RWD. Oh well, maybe next time.

Overall descending. Let me tell you, I charged that descent. Different bike be damned; single pivot be damned; I just went after it. And I must say I hauled ass. Not in that way when you're all sketchy and you think you're going fast, but you're actually going slow. In that way when you're in total control and the terrain scrolls by serenely, and your fast riding partners are way off the back. Since descending is so important, let me break it down further: Descending in snow: Better than usual. The bike felt much more controllable than my trusty Enduro, but some icy sections were still very sketchy. But ice is sketchy, plain and simple. Drops. The top of the trail made mellow, banked turns then dribbled over a series of ledges. Each time I launched the tires would slow noticeably, and they'd catch when they landed -- CHIRP! -- like the wheels on an airplane. I found this disconcerting at first, but I soon learned to shift my weight a bit farther back, and all was good with the world. Tight downhill corners. The trail dropped straight down the fall line then hung a hard right across the hill. I knew this corner was tight and loose. I set up wide, skidded the rear out, let go of the brakes then started to weight the front end to enter the turn. Before I knew it, I was exiting the turn. Whoosh, just like that. The Christini pulled right through, like an Audi Quatro on the gas. I charged the remaining switchbacks with abandon, and the bike kept surprising me with its consistent tracking and utter lack of drama. Steep, rough rock action. A bunch of riders stood around a silly looking rock section, wishing they hadn't just crapped their pants. I called out and dove in. The front wheel and fork are not exceptionally stiff, yet the bike tracked straight through the unnecessary roughness and random cambers. A truly active suspension would have eliminated some unnerving brake jack, but overall the bike rocked like a hurricane.  Fast corners. Near the bottom of the descent, the trail hugged the contour and opened up. I carried ridiculous speed across the straights and deep into the turns. I don't know why, but instead of braking I just leaned the bike over. Wow, it came around like a champ. As you might know, a leaning wheel develops a force called "camber thrust." I suspect the driven front tire multiplies this effect.

Fast corners. Near the bottom of the descent, the trail hugged the contour and opened up. I carried ridiculous speed across the straights and deep into the turns. I don't know why, but instead of braking I just leaned the bike over. Wow, it came around like a champ. As you might know, a leaning wheel develops a force called "camber thrust." I suspect the driven front tire multiplies this effect.

Graphic from your next book: Mastering Mountain Bike Skills. Bumpy, tight, flat corners At the end of the ride I charged down the rocky stream bed I'd climbed on the way out. I left it in the middle ring where the suspension would be most neutral, and the bike just freaking ripped. It stuck the sandy corners better than normal, and it tracked over the rocks as it had on the climb. What a fun ride: cool people, sweet trails and a capable bike. Who should buy one? What's great about it: With the AWD switched off the Christini feels like a normal bike. With the AWD on, it does things other bikes can't do. This comes at a cost of only 2.3 pounds, which means nothing in this day of 30-pound bikes and 15-pound Camelbaks. What's not cool but I can live with: 1) The noise. The gnashing gears make the bike feel cheap, and, like I said, you just KNOW they're stealing power. (BTW, I oiled the gears as Gayle suggested.) The thing is, in the situations where the AWD makes the most sense, you'll be too busy cranking or railing to notice the noise. The racket only bugged me in mellow sections where I didn't need the AWD. 2) The suspension. The single-pivot "Active Arc" suspension design works OK, but there are better solutions, especially at this price point. As I fought brake jack through a couple sections I thought, "If I just could attach this AWD to my Enduro ..." If Christini licenses a top-notch suspension design (FSR, VPP, etc.), that would eliminate one barrier to purchase. What's not so great about it: 1) It's different. As much as we mountain bikers like to think we're rebels, we're followers just like everyone else. Most of us have notions about how bikes should be, and the Christini just doesn't match. 2) It's not inexpensive. The frame and fork kit costs $2,675. A full bike with XT/LX goes for $3,375. For that much money you can get any proven design you want. Are you willing to try something completely new for that kind of coin? Today's mountain bikes work great. The Christini AWD system promises to make them work even better. One question is, who feels the need to step it up this high? I'll say the Christini AWD system will serve two types of riders: 1) Freaks who love hyper-technical climbing. 2) Gravity riders who demand and are willing to pay for ultimate handling. I can't say for sure without more testing (hint :), but I think a Christini AWD bike could rule in slalom and downhill. I can see riders hooking corners and tracking through roots, making up a second here and there, and finishing with great times. Christini is working on a downhill frame, so we'll find out soon enough. If you're curious check out www.christini.com and see if you can wrangle a test ride. Don't worry about the gears and stuff. Just pedal your brains out, dive into a corner and let your front wheel pull you into a new style of riding. |

If I don't start making money on this site, I'll have to get a real job.

Preserve Lee Likes Bikes Buy a 2005 calendar! |

|

Home Email Lee © 2004 Lee McCormack. All rights reserved. |